I enjoy myths a great deal, mostly because I like good stories, but also because myths are one of most effective means for understanding a foreign world of life, belief, and culture. People tell myths to teach their children what their people believe about God and about life, and to remind themselves of those things, in a way that is compelling and memorable. Thus, if you can understand a group’s myths, you can see the world through the eyes of that group. Once, in college, I spent the better part of a semester trying to learn Hindu theology through a textbook, only to find that I was able to do far more in less time by simply learning the most popular Hindu myths, and the meanings of the symbols they contained. So, to tell you about Cambodia, I thought I’d share a legend, but mostly, I just want to tell you a story about a monk, a princess, and some sea serpents.

Once upon a time, there was a Brahman—an Indian holy man—named Kambu. In addition to being a priest, Kambu was a

hermit, living a life of religious discipline in the high mountains. One

day, the gods told Kambu, to go to the far south, below the empire of the

Chinese, down into the lands of the barbarian tribes, and there find a

beautiful princess to take for his wife. Now, there are few commands more

welcome to a lonely old hermit than the order to go find a beautiful woman, so

Kambu hurried off on his journey. He travelled through the wild jungles of the steaming

south, coming to a large plain crisscrossed by a multitude of rivers and dotted

with the occasional large lake or stand of jungle. There, Kambu found native

tribes he expected, but he also found something he was not prepared to see: the

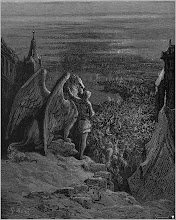

nagi. The nagi are a race of water snakes, but they are more like magical

sea serpents than they are like the snakes one might run across in an ordinary swamp.

They come in various shapes and sizes, with many of them having several

heads or extra tails, or horns or crests, and hundreds of sharp teeth. But,

despite their various forms, all nagi share a mystical nature, a fearsome

demeanor, and are extremely dangerous when provoked.

Looking among the tribesmen who lived in the land of the nagi, Kambu found no

princess. In his confusion, he sat down to meditate, and to watch the

strange nagi. It was then that Kambu saw his beautiful princess.

You see, when I said that nagi may come in all shapes and sizes, I meant

it. Like many of the mystical creatures of the East, the nagi need not even

look like water snakes to still be nagi. Apparently, they may stray so

far from their native forms as to appear mostly human, although they are still

nagi at heart. I would explain this to you, because of course I

understand perfectly how a creature can be both a river-dwelling reptile and a

divinely beautiful human woman of noble lineage, but that would ruin a good

chance for you to use your imagination.

However she came to be, this princess of the nagi was a beautiful woman

named Mera. Being a mystical and royal woman, Mera should have known

better than to throw in with an unwashed, road-weary stranger who had not a

penny to his name. Yet if there's one thing that a guru knows how to do

well, it's snake-charming, and for all her human aspect and magical nature,

Mera was still a serpent. So, Kambu caused her to fall in love with him

through magic of his own. Having fallen in love with one another, she

with his Hindu arts and he with her mystical beauty, the two became married,

and had many children. They shared their personal riches of knowledge,

and thus was born a tradition steeped in the magic and lore of the nagi and the

philosophies and devotions of the Brahman. Their children became lords of

the land, whose children in turn became the kings of the vast Angkor empire

that ruled over Southeast Asia for many years, building temples to the religion

of their father and protecting them with the figures and spirit of their

mother.

Whether

or not this legend is true, there is much in it that is true about

Cambodia. First of all, the nagi

represent many of the indigenous values and realities of the country. Although they themselves are part of Hinduism

and Buddhism, they have a special and ancient place in Cambodia. Like the dragons

of classical Europe, the nagi feature prominently in all the oldest stories of

Cambodia, forming a national symbol that evokes a primordial, essential

Cambodia. Nagi statues adorn many temples as symbolic guardians, like the

gargoyles that cover the cathedrals of France.

The water-dwelling nature of the nagi evoke the Cambodian relationship

to the country’s rivers and lakes: in the way that many cultures worshipped the

sun or sky as the source of life and the place of the gods, ancient and

classical Cambodians reverenced the waters, whence came the rice and fish that

have always fed the people. Any wealth Cambodia has ever known likewise came

from the rivers, through selling crops grown on the rivers and doing commerce

along the waterways, so it is not surprising that, also like European dragons,

nagi guard vast treasure troves. The dangerousness of the nagi, too, is

representative of the Cambodian understanding of water, embodying the way in

which the river may flood and destroy whole villages in minutes.

The

union of Kambu and Mera also symbolizes one of the most fundamental truths of

Cambodian culture. This union is

reminiscent of the name of the Cambodian people, who are called the Khmer, a

name that combines Kambu and Mera.

Furthermore, Kambu’s name itself echoes the native name of the country,

with is Kambuja or Kampuchea. The culture of Kambu’s land developed largely out

of the way in which first the ancient Cambodian tribes, then the various

empires of Cambodia, interpreted the philosophy and religion of the Indian

traders who came to their country in its infancy. Those traders brought with them the art,

tools, spices, religion, and philosophies of India and established them through

permanent towns that became cultural centers. However, the Cambodians

refused to adopt Indian culture wholesale, instead infusing their new-found civilization with many of their own traditions and practices. Thus, what it means to be Cambodian is summed

up in the marriage of the Indian Brahman to the naga princess. And, as for that priest and his princess,

they, of course, lived happily ever after.